Thursday, October 31, 2019

JeffTells: MANNY PACQUIAO'S GREATEST FIGHT HIGHLIGHTS

JeffTells: MANNY PACQUIAO'S GREATEST FIGHT HIGHLIGHTS: Pacquiao vs Rios Fight highlights and what had Pacquiao's very angry. The Main Event. Manny Pacquiao vs Marco Barrera Full Figh...

JeffTells: MUSIC VIDEOS

JeffTells: MUSIC VIDEOS: #Originaly BINALEWALA Kahit Ayaw MO na I Can't Let Go Wonderful song for Valentines day. INSTRUMENTAL &...

JeffTells: History of the Philippine

JeffTells: History of the Philippine: "MAHARLIKA" The lost kingdom Ang buong arkipelago ng pilipinas ay pag mamay ari ng iisang pamilya lamang? Kalokohan pano ...

JeffTells: Travel and Tour

JeffTells: Travel and Tour: DAKU ISLAND @ SIARGAO Daku Island is a part of the island hopping tour that also includes Guyam and Naked Islands. Daku is the bi...

JeffTells: Travel and Tour

JeffTells: Travel and Tour: DAKU ISLAND @ SIARGAO Daku Island is a part of the island hopping tour that also includes Guyam and Naked Islands. Daku is the bi...

JeffTells: This Letter Reveals Who Really Killed Andres Bonif...

JeffTells: This Letter Reveals Who Really Killed Andres Bonif...: RG 5248 Without a doubt, Emilio Aguinaldo is certainly one of the most polarizing figures in Philippine history. While his achiev...

JeffTells: JeffTells: This Letter Reveals Who Really Killed A...

JeffTells: JeffTells: This Letter Reveals Who Really Killed A...: JeffTells: This Letter Reveals Who Really Killed Andres Bonif... : RG 5248 Without a doubt, Emilio Aguinaldo is certainly one of the most...

Saturday, October 19, 2019

Thursday, October 17, 2019

JeffTells: This Letter Reveals Who Really Killed Andres Bonif...

JeffTells: This Letter Reveals Who Really Killed Andres Bonif...: RG 5248 Without a doubt, Emilio Aguinaldo is certainly one of the most polarizing figures in Philippine history. While his achiev...

Wednesday, October 16, 2019

Monday, October 14, 2019

JeffTells: This Letter Reveals Who Really Killed Andres Bonif...

JeffTells: This Letter Reveals Who Really Killed Andres Bonif...: RG 5248 Without a doubt, Emilio Aguinaldo is certainly one of the most polarizing figures in Philippine history. While his achiev...

This Letter Reveals Who Really Killed Andres Bonifacio

RG 5248

Without a doubt, Emilio Aguinaldo is certainly one of the most

polarizing figures in Philippine history. While his achievements on the

battlefield cannot be discounted, Miong’s legacy continues to be stained with

the deaths of Andres Bonifacio and Antonio Luna—two revolutionary figures whose

demise will always be connected to his name.

It’s surprising to know for some that while Aguinaldo denied having

anything to do with Luna’s murder until his dying day, he readily confessed to

having ordered Bonifacio’s execution.

On March 22, 1948 (the day before his birthday), Aguinaldo released a letter

saying he was indeed the one who ordered the execution of Bonifacio and his

brother Procopio (the letter was certified authentic by Teodoro Agoncillo and

published in his book ‘Revolt of the Masses’).

In his letter bearing his signature, Aguinaldo said that while he

initially commuted the brothers’ death sentence to banishment, he was prevailed

upon by his generals Mariano Noriel and Pio del Pilar who were part of his

Council of War to carry out the execution for the country’s sake.

“Kung ibig po ninyong magpatuloy ang kapanatagan ng pamahalaang

mapanghimagsik, at kung ibig ninyong mabuhay pa tayo, ay inyo pong bawiin ang

iginawad na indukto sa magkapatid na iyan,” they told him.

In reply, Aguinaldo said: “Dahil dito’y aking binawi at inutos ko kay

Heneral Noriel na ipatupad ang kahatulan ng Consejo de Guerra, na barilin ang

magkapatid, alang-alang sa kapanatagan ng bayan.”

So, was Aguinaldo to blame for everything?

According to historian Xiao Chua, while Miong may indeed have had his

faults, the blame should be also placed on his inner circle especially the

elite for their negative influence on the country’s youngest president who was

undeniably a greenhorn in the world of politics.

Remember, the only offices Aguinaldo held before becoming president was

cabeza de barangay of Binakayan and gobernadorcillo capitan municipal of Cavite

el Viejo.

“We have to consider that he was 28 or 29 when he became president,”

Chua said. “He was surrounded by traditional politicians.”

“It was the elite system—“elite democracy” that killed the Supremo,” he

added.

Credits to filipiknow.net.

Thank you for reading...

Sunday, October 13, 2019

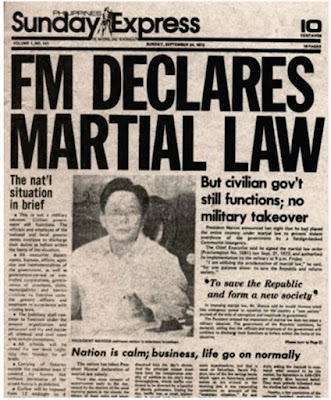

JeffTells: MARTIAL LAW (1972-1981)

JeffTells: MARTIAL LAW (1972-1981): Martial Law (1972–1981) Main article: Martial law under Ferdinand Marcos September 24, 1972 issue of the Sunday edition of ...

JeffTells: MANNY PACQUIAO'S GREATEST FIGHT HIGHLIGHTS

JeffTells: MANNY PACQUIAO'S GREATEST FIGHT HIGHLIGHTS: Pacquiao vs Rios Fight highlights and what had Pacquiao's very angry. The Main Event. Manny Pacquiao vs Marco Barrera Full Figh...

JeffTells: The Historical of Marcos Regime

JeffTells: The Historical of Marcos Regime: The Marcos administration (1965–72) First term In 1965, Ferdinand Marcos won the presidential election and became the 1...

JeffTells: JeffTells: The Historical of Marcos Regime

JeffTells: JeffTells: The Historical of Marcos Regime: JeffTells: The Historical of Marcos Regime : The Marcos administration (1965–72) First term In 1965, Ferdinand Marcos won the presid...

JeffTells: MARTIAL LAW (1972-1981)

JeffTells: MARTIAL LAW (1972-1981): Martial Law (1972–1981) Main article: Martial law under Ferdinand Marcos September 24, 1972 issue of the Sunday edition of ...

Friday, October 11, 2019

JeffTells: MARTIAL LAW (1972-1981)

JeffTells: MARTIAL LAW (1972-1981): Martial Law (1972–1981) Main article: Martial law under Ferdinand Marcos September 24, 1972 issue of the Sunday edition of ...

JeffTells: MARTIAL LAW (1972-1981)

JeffTells: MARTIAL LAW (1972-1981): Martial Law (1972–1981) Main article: Martial law under Ferdinand Marcos September 24, 1972 issue of the Sunday edition of ...

MARTIAL LAW (1972-1981)

Main article: Martial

law under Ferdinand Marcos

September 24, 1972 issue of the Sunday edition of the

Philippine Daily Express

Proclamation 1081

Marcos' declaration of martial law became known to the public on

September 23, 1972 when his Press Secretary, Francisco Tatad, announced on

Radio that Proclamation № 1081,

which Marcos had supposedly signed two days earlier on September 21, had come

into force and would extend Marcos's rule beyond the constitutional two-term

limit. Ruling by decree, he almost dissolved press freedom and

other civil liberties to

add propaganda machine, closed down Congress and media establishments, and

ordered the arrest of opposition leaders and militant activists, including

senators Benigno Aquino Jr., Jovito Salonga and Jose Diokno. However, unlike Ninoy Aquino's

senator colleagues who were detained without charges, Ninoy, together with

communist NPA leaders Lt Corpuz and Bernabe Buscayno, was charged with murder,

illegal possession of firearms and subversion. Marcos claimed that martial

law was the prelude to creating his Bagong Lipunan, a "New

Society" based on new social and political values.

Bagong Lipunan (New Society)

Marcos had a vision of a Bagong Lipunan (New Society)

similar to Indonesian president Suharto's "New Order

administration", China leader Mao Zedong's Great Leap Forward

and Korean Kim Il-Sung's Juche.

He used the years of martial law to implement this vision. According to

Marcos's book Notes on the New Society, it was a movement urging

the poor and the privileged to work as one for the common goals of society and

to achieve the liberation of the Filipino people through self-realization.

University

of the Philippines Diliman economics professor and former NEDA Director-General

Dr. Gerardo Sicat, an MIT Ph.D.

graduate, portrayed some of Martial Law's effects as follows:

Economic reforms suddenly became

possible under martial law. The powerful opponents of reform were silenced and

the organized opposition was also quilted. In the past, it took enormous

wrangling and preliminary stage-managing of political forces before a piece of

economic reform legislation could even pass through Congress. Now it was

possible to have the needed changes undertaken through presidential decree.

Marcos wanted to deliver major changes in an economic policy that the

government had tried to propose earlier.

The enormous shift in the mood of the

nation showed from within the government after martial law was imposed. The

testimonies of officials of private chambers of commerce and of private

businessmen dictated enormous support for what was happening. At least, the

objectives of the development were now being achieved...

Japanese imperial army soldier Hiroo Onoda offering his military sword

to Marcos on the day of his surrender on March 11, 1974

The Marcos regime instituted a

mandatory youth organization, known as the Kabataang Barangay,

which was led by Marcos's eldest daughter Imee. Presidential Decree 684,

enacted in April 1975, required that all youths aged 15 to 18 be sent to remote

rural camps and do volunteer work.

1973 Martial Law Referendum

Martial Law was put on vote in July 1973

in the 1973

Philippine Martial Law referendum and was marred with

controversy resulting to 90.77% voting yes and 9.23% voting no.

Rolex 12 and the military

Along with Marcos, members of

his Rolex 12 circle like Defense

Minister Juan Ponce Enrile,

Chief of Staff of the Philippine Constabulary Fidel Ramos, and Chief of Staff of the Armed

Forces of the Philippines Fabian Ver were the chief administrators

of martial law from 1972 to 1981, and the three remained President Marcos's

closest advisers until he was ousted in 1986. Other peripheral members of

the Rolex 12 included Eduardo

"Danding" Cojuangco Jr. and Lucio Tan.

Between 1972 and 1976, Marcos

increased the size of the Philippine military from 65,000 to 270,000 personnel,

in response to the fall of South Vietnam to the communists and the growing tide

of communism in South East Asia. Military officers were placed on the boards of

a variety of media corporations, public utilities, development projects, and

other private corporations, most of whom were highly educated and well-trained

graduates of the Philippine Military Academy. At the same time, Marcos made

efforts to foster the growth of a domestic weapons manufacturing industry and

heavily increased military spending.

Many human rights abuses were

attributed to the Philippine

Constabulary which was then headed by future president Fidel Ramos. The Civilian

Home Defense Force, a precursor of Civilian Armed Forces

Geographical Unit (CAFGU), was organized by President Marcos to battle with the

communist and Islamic insurgency problem, has particularly been accused of

notoriously inflicting human right violations on leftists, the NPA, Muslim

insurgents, and rebels against the Marcos government. However, under

martial law the Marcos administration was able to reduce violent urban crime,

collect unregistered firearms, and suppress communist insurgency in some areas.

U.S. foreign policy and martial law under Marcos

By 1977, the armed forces had

quadrupled and over 60,000 Filipinos had been arrested for political reasons.

In 1981, Vice President George H. W. Bush praised Marcos for his

"adherence to democratic principles and to the democratic processes". No

American military or politician in the 1970s ever publicly questioned the

authority of Marcos to help fight communism in South East Asia.

From the declaration of martial law

in 1972 until 1983, the U.S. government provided $2.5 billion in bilateral

military and economic aid to the Marcos regime, and about $5.5 billion through

multilateral institutions such as the World Bank.

In a 1979 U.S. Senate report,

it was stated that U.S. officials were aware, as early as 1973, that Philippine

government agents were in the United States to harass Filipino dissidents. In

June 1981, two anti-Marcos labor activists were assassinated outside of a union

hall in Seattle. On at least one occasion, CIA agents

blocked FBI investigations

of Philippine agents.

Withdrawal of Taiwan relations in favor of the People's

Republic of China.

Main articles: Philippines–Taiwan

relations and China–Philippines

relations

Prior to the Marcos administration,

the Philippine government had maintained a close relationship with the Kuomintang-ruled Republic of China (ROC) government which

had fled to the island of Taiwan,

despite the victory of the Communist Party of

China in the 1949 Chinese

Communist Revolution. Prior administrations had seen the People's

Republic of China (PRC) as a security threat, due to its

financial and military support of Communist rebels in the country.

By 1969, however, Ferdinand Marcos

started publicly asserting the need for the Philippines to establish a

diplomatic relationship with the People's

Republic of China. In his 1969 State of the Nation Address, he said:

We, in Asia must strive toward a

modus vivendi with Red China. I reiterate this need, which is becoming more

urgent each day. Before long, Communist China will have increased its striking

power a thousand fold with a sophisticated delivery system for its nuclear

weapons. We must prepare for that day. We must prepare to coexist peaceably

with Communist China.

— Ferdinand Marcos, January 1969

In June 1975, President Marcos went

to the PRC and signed a Joint Communiqué normalizing relations between the

Philippines and China. Among other things, the Communiqué recognizes that

"there is but one China and that Taiwan is an integral part of Chinese

territory…" In turn, Chinese Prime Minister Zhou Enlai also pledged that China would

not intervene in the internal affairs of the Philippines nor seek to impose its

policies in Asia, a move which isolated the local communist movement that China

had financially and militarily supported.

The Washington Post in an interview with former Philippine Communist Party

Officials, revealed that, "they (local communist party officials) wound up

languishing in China for 10 years as unwilling "guests" of the

(Chinese) government, feuding bitterly among themselves and with the party

leadership in the Philippines".

The government subsequently captured

NPA leaders Bernabe Buscayno in

1976 and Jose Maria Sison in

1977.

First parliamentary elections after martial law declaration

The 1978

Philippine parliamentary election was held on April 7, 1978 for

the election of the 166 (of the 208) regional representatives to the Interim Batasang

Pambansa (the nation's first parliament). The elections were

participated by several parties including Ninoy Aquino's newly formed party,

the Lakas ng Bayan (LABAN)

and the regime's party known as the Kilusang Bagong

Lipunan (KBL).

The Ninoy Aquino's LABAN party

fielded 21 candidates for the Metro Manila area including Ninoy himself and

Alex Boncayao, who later was associated with Filipino communist death squad

Alex Boncayao Brigade that killed U.S. army Colonel James N. Rowe. All of the party's candidates,

including Ninoy, lost in the election.

Marcos's KBL party won 137 seats,

while Pusyon Bisaya led by Hilario Davide Jr.,

who later became the Minority Floor Leader, won 13 seats.

Prime Minister

In 1978, the position returned when

Ferdinand Marcos became Prime Minister. Based on Article 9 of

the 1973 constitution, it had broad executive powers that would be typical of

modern prime ministers in other countries. The position was the official head

of government, and the commander-in-chief of the armed forces. All of the

previous powers of the President from the 1935 Constitution were transferred to

the newly restored office of Prime Minister. The Prime Minister also acted as head

of the National Economic Development Authority. Upon his re-election to the

Presidency in 1981, Marcos was succeeded as Prime Minister by an

American-educated leader and Wharton graduate, Cesar Virata, who was elected as an

Assemblyman (Member of the Parliament) from Cavite in 1978. He is the eponym of

the Cesar Virata School of Business, the business school of the University

of the Philippines Diliman.

Proclamation No. 2045

After putting in force amendments to the constitution, legislative

action, and securing his sweeping powers and with the Batasan, his supposed

successor body to the Congress, under his control, President Marcos

issued Proclamation 2045, which technically "lifted"

martial law, on January 17, 1981.

However, the suspension of the

privilege of the writ of habeas corpus continued

in the autonomous regions of Western Mindanao and Central Mindanao. The opposition dubbed the

lifting of martial law as a mere "face lifting" as a precondition to

the visit of Pope John Paul II.

Third term (1981–1986)

Main article: 1981 Philippine presidential election and referendum

President Ferdinand E. Marcos in Washington in 1983.

We love your adherence to democratic

principles and to the democratic process, and we will not leave you in

isolation.

— U.S. Vice President George H. W. Bush during Ferdinand E.

Marcos inauguration, June 1981

On June 16, 1981, six months after

the lifting of martial law, the first presidential election in twelve years was

held. President Marcos ran and won a massive victory over the other candidates.

The major opposition parties, the United

Nationalists Democratic Organizations (UNIDO), a coalition of

opposition parties and LABAN, boycotted the elections.

After the lifting of Martial Law, the

pressure on the Communist CPP-NPA alleviated. The group was able to return to

urban areas and form relationships with legal opposition organizations, and

became increasingly successful in attacks against the government throughout the

country. The violence inflicted by the communists reached its peak in 1985

with 1,282 military and police deaths and 1,362 civilian deaths.

Aquino's assassination

Main article: Assassination

of Benigno Aquino Jr.

On August 21, 1983, opposition

leader Benigno Aquino Jr. was

assassinated on the tarmac at Manila

International Airport. He had returned to the Philippines after

three years in exile in the United States, where he had a heart bypass

operation to save his life after Marcos allowed him to leave the Philippines to

seek medical care. Prior to his heart surgery, Ninoy, along with his two

co-accused, NPA leaders Bernabe Buscayno (Commander Dante) and

Lt. Victor Corpuz, were sentenced to death by a military commission on charges

of murder, illegal possession of firearms and subversion.

A few months before his

assassination, Ninoy had decided to return to the Philippines after his

research fellowship from Harvard University had

finished. The opposition blamed Marcos directly for the assassination while

others blamed the military and his wife, Imelda. Popular speculation pointed to

three suspects; the first was Marcos himself through his trusted military chief

Fabian Ver; the second theory pointed to his wife Imelda who had her own

burning ambition now that her ailing husband seemed to be getting weaker, and the

third theory was that Danding Cojuangco planned

the assassination because of his own political ambitions. The 1985

acquittals of Chief of Staff General Fabian Ver as well as other high-ranking

military officers charged with the crime were widely seen as a whitewash and

a miscarriage of justice.

On November 22, 2007, Pablo Martinez,

one of the convicted suspects in the assassination of Ninoy Aquino Jr. alleged

that it was Ninoy Aquino Jr.'s relative, Danding Cojuangco, cousin of his wife

Corazon Cojuangco Aquino, who ordered the assassination of Ninoy Aquino Jr.

while Marcos was recuperating from his kidney transplant. Martinez also alleged

only he and Galman knew of the assassination, and that Galman was the actual

shooter, which is not corroborated by other evidence of the case.

Impeachment attempt.

In August 1985, 56 Assemblymen signed

a resolution calling for the impeachment of President Marcos for

alleged diversion of U.S. aid for personal use, citing a July 1985 San Jose Mercury News exposé

of the Marcos's multimillion-dollar investment and property holdings in the

United States.

The properties allegedly amassed by

the First Family were the Crown Building, Lindenmere Estate, and a number of

residential apartments (in New Jersey and New York), a shopping center in New

York, mansions (in London, Rome and Honolulu), the Helen Knudsen Estate in

Hawaii and three condominiums in San Francisco, California.

The Assembly also included in the

complaint the misuse and misapplication of funds "for the construction of

the Manila Film Center,

where X-rated and pornographic films are exhibited, contrary to public

morals and Filipino customs and traditions." The impeachment attempt

gained little real traction, however, even in the light of this incendiary

charge; the committee to which the impeachment resolution was referred did not

recommend it, and any momentum for removing Marcos under constitutional

processes soon died.

Thanks for reading.

JeffTells: The Historical of Marcos Regime

JeffTells: The Historical of Marcos Regime: The Marcos administration (1965–72) First term In 1965, Ferdinand Marcos won the presidential election and became the 1...

JeffTells: The Historical of Marcos Regime

JeffTells: The Historical of Marcos Regime: The Marcos administration (1965–72) First term In 1965, Ferdinand Marcos won the presidential election and became the 1...

The Historical of Marcos Regime

The Marcos administration (1965–72)

First term

In 1965, Ferdinand Marcos won the presidential

election and became the 10th President of the Philippines. His first term

was marked with increased industrialization and the creation of solid

infrastructures nationwide, such as the North Luzon Expressway and the Maharlika Highway. Marcos did this by appointing a

cabinet composed mostly of technocrats and intellectuals, by

increasing funding to the Armed Forces and

mobilizing them to help in construction. Marcos also established schools and

learning institutions nationwide, more than the combined total of those established

by his predecessors.

In 1968, Senator Benigno S. Aquino Jr. warned that

Marcos was on the road to establishing "a garrison state" by

"ballooning the armed forces budget", saddling the defense

establishment with "overstaying generals" and "militarizing our

civilian government offices". These were prescient comments in the light

of events that would happen in the following decade.[3] Marcos also sent 10,450

Filipino soldiers to Vietnam during his term, under the PHILCAG (Philippine

Civic Action Group). Fidel Ramos, who was later to become the 12th

President of the Philippines in 1992, was a part of this expeditionary force.

Second term

In 1969, Marcos ran for a

second term (allowable under the 1935 constitution then in effect), and won against

11 other candidates.

Marcos' second term was marked by

economic turmoil brought about by factors both external and internal, a

restless student body who demanded educational reforms, a rising crime rate,

and a growing Communist insurgency, among other things.

Ferdinand Marcos, president from 1965–1986.

At one point, student activists took

over the Diliman campus of the University of the Philippines and declared it a

free commune, which lasted for a while before the government dissolved it.

Violent protesting continued over the next few years until the declaration of

martial law in 1972. The event was popularly known as the First Quarter Storm.

During the First Quarter Storm in 1970, the

line between leftist activists and communists became increasingly blurred, as a

significant number of Kabataang Makabayan ('KM')

advanced activists joined the party of the Communist Party also founded

by Jose Maria Sison. KM members protested in front

of Congress, throwing a coffin, a stuffed alligator, and stones at Ferdinand

and Imelda Marcos after his State of the Nation Address. On the presidential

palace, activists rammed the gate with a fire truck and once the gate broke and

gave way, the activists charged into the Palace grounds tossing rocks,

pillboxes, Molotov cocktails. In front of the US embassy, protesters

vandalized, burned, and damaged the embassy lobby resulting in a strong protest

from the U.S. Ambassador. The KM protests ranged from 50,000 to 100,000 in

number per weekly mass action. In the aftermath of the January 1970 riots,

at least two activists were confirmed dead and several were injured by the

police. The mayor of Manila at the time, Antonio Villegas, commended the Manila Police District for their

"exemplary behavior and courage" and protecting the First Couple long

after they have left. The death of the activists was seized by the Lopez

controlled Manila Times and Manila Chronicle, blaming Marcos and added fire to

the weekly protests. Students declared a week-long boycott of classes and

instead met to organize protest rallies.

Rumors of coup d'état were also

brewing. A report of the U.S. Senate Foreign Relations Committee said that

shortly after the 1969 Philippine

presidential election, a group composed mostly of retired

colonels and generals organized a revolutionary junta to first discredit

President Marcos and then kill him. As described in a document given to the

committee by Philippine Government official, key figures in the plot were Vice

President Fernando Lopez and Sergio Osmena Jr., whom Marcos defeated in the

1969 election.Marcos even went to the U.S. embassy to dispel rumors that the

U.S. embassy is supporting a coup d'état which the opposition liberal party was

spreading. While the report obtained by the NY Times speculated saying that

story could be used by Marcos to justify Martial Law, as early as December 1969

in a message from the U.S. Ambassador to the U.S. Assistant Secretary of State,

the U.S. Ambassador said that most of the talk about revolution and even

assassination has been coming from the defeated opposition, of which Adevoso

(of the Liberal Party) is a leading activist. He also said that the information

he has on the assassination plans are 'hard' or well-sourced and he has to make

sure that it reached President Marcos.

In light of the crisis, Marcos wrote

an entry in his diary in January 1970. "I have several options. One

of them is to abort the subversive plan now by the sudden arrest of the

plotters. But this would not be accepted by the people. Nor could we get the

Huks (Communists), their legal cadres and support. Nor the MIM (Maoist

International Movement) and other subversive [or front] organizations, nor

those underground. We could allow the situation to develop naturally then after

massive terrorism, wanton killings and an attempt at my assassination and a

coup d’etat, then declare martial law or suspend the privilege of the writ of

habeas corpus – and arrest all including the legal cadres. Right now I am

inclined towards the latter."

Plaza Miranda bombing

Main article: Plaza Miranda bombing

On August 21, 1971, the Liberal Party held a

campaign rally at the Plaza Miranda to proclaim their Senatorial

bets and their candidate for the Mayoralty of Manila. Two grenades were

reportedly tossed on stage, injuring almost everybody present. As a result,

Marcos suspended the writ of habeas corpus to arrest

those behind the attack. He rounded up a list of supposed suspects, Escabas,

and other undesirables to eliminate rivals in the Liberal Party.

Based on interviews of The Washington Post with former

Communist Party of the Philippines Officials, it was revealed that "the

(Communist) party leadership planned -- and three operatives carried out -- the

attack in an attempt to provoke government repression and push the country to

the brink of revolution... (Communist Party Leader) Sison had calculated that

Marcos could be provoked into cracking down on his opponents, thereby driving

thousands of political activists into the underground, the former party

officials said. Recruits were urgently needed, they said, to make use of a

large influx of weapons and financial aid that China had already agreed to

provide."

Martial law (1972–1981)

Main article: Martial law under

Ferdinand Marcos

On September 23, 1972, then-Defense

Minister Juan Ponce Enrile was ambushed while en route

home. This assassination attempt together with the general citizen

disquiet, were used by Marcos as reasons to issue Presidential Proclamation No.

1081, proclaiming a state of martial law in the Philippines on September 21. The

assassination attempt was widely believed to have been staged; Enrile himself

admitted to the assassination attempt to have been staged but he would later

retract his claim. Rigoberto Tiglao, former press secretary and a former

communist incarcerated during the martial law, argued that the liberal and

communist parties provoked martial law imposition. Enrile said that

"The most significant event that made President Marcos decide to declare

martial law was the MV Karagatan incident on July 1972. It was the turning

point. The MV Karagatan involved the infiltration of high powered rifles,

ammunition, 40-millimeter rocket launchers, rocket projectiles, communications

equipment, and other assorted war materials by the CPP-NPA-NDF on the Pacific

side of Isabela in Cagayan Valley." The weapons were shipped from

Communist China which at that time was exporting the communist revolution and

supported the NPA's goal to overthrow the government.

Marcos, who thereafter ruled by

decree, curtailed press freedom and other civil liberties, abolished Congress, controlled media

establishments, and ordered the arrest of opposition leaders and militant

activists, including his staunchest critics Senators Benigno Aquino Jr. and Jose W. Diokno, virtually turning the Philippines

into a totalitarian dictatorship with Marcos

as its Supreme Leader. Initially, the declaration of martial law was well

received, given the social turmoil of the period. Crime rates decreased

significantly after a curfew was implemented. Political opponents were allowed

to go into exile. As martial law went on for the next nine years, the excesses

committed by the military increased. In total, there were 3,257 extrajudicial

killings, 35,000 individual tortures, and 70,000 were incarcerated. It is also

reported that 737 Filipinos disappeared between 1975 and 1985.

I am president. I am the most powerful man in the Philippines.

All that I have dreamt of I have. More accurately, I have all the material

things I want of life — a wife who is loving and is a partner in the things I

do, bright children who will carry my name, a life well lived — all. But I feel

a discontent.

— Ferdinand Marcos

Though it was claimed that Martial

law was no military take-over of the government, the immediate reaction of some

sectors of the nation was of astonishment and dismay, for even it was claimed

that the gravity of the disorder, lawlessness, social injustice, youth and

student activism, and other disturbing movements had reached a point of peril,

they felt that martial law over the whole country was not yet warranted. Worse,

political motivations were ascribed to be behind the proclamation, since the

then constitutionally non-extendable term of President Marcos was about to

expire. This suspicion became more credible when opposition leaders and

outspoken anti-administration media people were immediately placed under

indefinite detention in military camps and other unusual restrictions were

imposed on travel, communication, freedom of speech and the press, etc. In a

word, the martial law regime was anathema to no small portion of the populace.

It was in the light of the above

circumstances and as a means of solving the dilemma aforementioned that the

concept embodied in Amendment No. 6 was born in the Constitution of 1973. In

brief, the central idea that emerged was that martial law might be earlier

lifted, but to safeguard the Philippines and its people against any abrupt

dangerous situation which would warrant the some exercise of totalitarian

powers, the latter must be constitutionally allowed, thereby eliminating the

need to proclaim martial law and its concomitants, principally the assertion by

the military of prerogatives that made them appear superior to the civilian

authorities below the President. In other words, the problem was what may be

needed for national survival or the restoration of normalcy in the face of a

crisis or an emergency should be reconciled with the popular mentality and

attitude of the people against martial law.

In a speech before his fellow alumni

of the University of the Philippines College of Law, President Marcos declared

his intention to lift martial law by the end of January 1981.

The reassuring words for the skeptic

came on the occasion of the University of the Philippines law alumni reunion on

December 12, 1980 when the President declared: "We must erase once and for

all from the public mind any doubts as to our resolve to bring martial law to

an end and to minister to an orderly transition to parliamentary

government." The apparent forthright irrevocable commitment was cast at

the 45th anniversary celebration of the Armed Forces of the Philippines on

December 22, 1980 when the President proclaimed: "A few days ago,

following extensive consultations with a broad representation of various

sectors of the nation and in keeping with the pledge made a year ago during the

seventh anniversary of the New Society, I came to the firm decision that

martial law should be lifted before the end of January, 1981, and that only in

a few areas where grave problems of public order and national security continue

to exist will martial law continue to remain in force."

After the lifting of martial law,

power remained concentrated with Marcos. One scholar noted how Marcos

retained "all martial law decrees, orders, and law-making powers,"

including powers that allowed him to jail political opponents.

Human rights abuses

The martial law era under Marcos was

marked by plunder, repression, torture, and atrocity. As many as 3,257

were murdered, 35,000 tortured, and 70,000 illegally detained according to

estimates by historian Alfred McCoy. One journalist described the

Ferdinand Marcos Administration as "a grisly one-stop shop for human

rights abuses, a system that swiftly turned citizens into victims by dispensing

with inconvenient requirements such as constitutional protections, basic

rights, due process, and evidence."

Economy

According to World Bank Data, the

Philippine's Gross Domestic Product quadrupled from $8 billion in 1972 to

$32.45 billion in 1980, for an inflation-adjusted average growth rate of 6% per

year. Indeed, according to the U.S. based Heritage Foundation, the Philippines

enjoyed its best economic development since 1945 between 1972 and 1980. The

economy grew amidst the two severe global oil shocks following the 1973 oil crisis and 1979 energy crisis - oil price

was $3 / barrel in 1973 and $39.5 in 1979, or a growth of 1200% which drove

inflation. Despite the 1984-1985 recession, GDP on a per capita basis more than

tripled from $175.9 in 1965 to $565.8 in 1985 at the end of Marcos' term,

though this averages less than 1.2% a year when adjusted for inflation. The

Heritage Foundation pointed out that when the economy began to weaken 1979, the

government did not adopt anti-recessionist policies and instead launched risky

and costly industrial projects.

The government had a cautious

borrowing policy in the 1970s. Amidst high oil prices, high interest

rates, capital flight, and falling export prices of sugar and coconut, the

Philippine government borrowed a significant amount of foreign debt in the

early 1980s. The country's total external debt rose from US$2.3 billion in

1970 to US$26.2 billion in 1985. Marcos' critics charged that policies have

become debt-driven, along with corruption and plunder of public funds by Marcos

and his cronies. This held the country under a debt-servicing crisis which is

expected to be fixed by only 2025. Critics have pointed out an elusive state of

the country's development as the period is marred by a sharp devaluing of the

Philippine Peso from 3.9 to 20.53. The overall economy experienced a slower

growth GDP per capita, lower wage conditions and higher unemployment especially

towards the end of Marcos' term after the 1983–1984 recession. The recession

was triggered largely by political instability following Ninoy's assassination, high

global interest rates, Severe global economic recession, and a significant increase in global oil

price, the latter three of which affected all indebted countries

in Latin America, Europe, and the

Philippines was not exempted. Critics claimed that poverty incidence grew

from 41% in the 1960s at the time Marcos took the Presidency to 59% when he was

removed from power.

The period is sometimes described as

a golden age for the country's economy. However, by the period's end, the

country was experiencing a debt crisis, extreme poverty, and severe

underemployment. On the island of Negros, one-fifth of the children under six

were seriously malnourished.

Corruption, plunder, and crony capitalism

The Philippines under martial law

suffered from massive and uncontrolled corruption.

Some estimates, including that by the

World Bank, put the Marcos family's stolen wealth at USD10 billion.

Plunder was achieved through the

creation of government monopolies, awarding loans to cronies, forced takeover

of public and private enterprises, direct raiding of the public treasury,

issuance of Presidential decrees that enabled cronies to amass wealth,

kickbacks and commissions from businesses, use of dummy corporations to launder

money abroad, skimming of international aid, and hiding of wealth in bank

accounts overseas.

Parliamentary elections

The first formal elections since 1969

for an interim Batasang Pambansa (National Assembly) were held

on April 7, 1978. Sen. Aquino, then in jail, decided to run as leader of his

party, the Lakas ng Bayan party, but they did not win any

seats in the Batasan, despite public support and their apparent

victory. The night before the elections, supporters of the LABAN party showed

their solidarity by setting up a "noise barrage" in Manila, creating

noise the whole night until dawn.

The Fourth Republic (1981–1986)

The opposition boycotted the

June 16, 1981 presidential elections, which pitted Marcos and his Kilusang Bagong Lipunan party against

retired Gen. Alejo Santos of the Nacionalista Party. Marcos won by a

margin of over 16 million votes, which constitutionally allowed him to have

another six-year term. Finance Minister Cesar Virata was elected as Prime Minister

by the Batasang Pambansa.

In 1983, opposition leader Benigno "Ninoy" Aquino Jr. was assassinated at Manila International Airport upon his

return to the Philippines after a long period of exile in the United States.

This coalesced popular dissatisfaction with Marcos and began a series of

events, including pressure from the United States, that culminated in a snap

presidential election on February 7, 1986. The opposition united under Aquino's

widow, Corazon Aquino, and Salvador Laurel, head of the United Nationalists

Democratic Organizations (UNIDO). The election was

marred by widespread reports of violence and tampering with results by both

sides.

The official election canvasser,

the Commission on

Elections (COMELEC), declared Marcos the winner, despite a walk-out

staged by disenfranchised computer technicians on February 9. According to the COMELEC's

final tally, Marcos won with 10,807,197 votes to Aquino's 9,291,761 votes. By

contrast, the partial 70% tally of NAMFREL, an accredited poll watcher, said

Aquino won with 7,835,070 votes to Marcos's 7,053,068.

End of the Marcos regime

See also: 1986 Philippine

presidential election

The fraudulent result was not

accepted by Aquino and her supporters. International observers, including a

U.S. delegation led by Senator Richard Lugar, denounced the official results.

General Fidel Ramos and Defense Minister Juan Ponce Enrile then withdrew their

support for the administration, defecting and barricading themselves

within Camp Crame. This resulted in that

peaceful 1986 EDSA Revolution that forced

Marcos into exile in Hawaii while Corazon Aquino became the 11th President of

the Philippines on February 25, 1986. Under Aquino, the Philippines would adopt

a new constitution, ending the Fourth Republic and ushering in the beginning of

the Fifth Republic.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)

HISTORY OF THE PHILIPPINE

JeffTells: THE 30th SOUTH EAST ASIAN GAMES 2019 OPENING CEREM...

JeffTells: THE 30th SOUTH EAST ASIAN GAMES 2019 OPENING CEREM... : The 30th SEA Games grand opening ceremony with President Rodrigo Duterte ...

-

Martial Law (1972–1981) Main article: Martial law under Ferdinand Marcos September 24, 1972 issue of the Sunday edition of ...

-

Ferdinand E. Marcos, The Richest Man in History IT IS TIME The Cojuangco-Aquino Family envy Ferdinand Mar...

-

The Marcos administration (1965–72) First term In 1965, Ferdinand Marcos won the presidential election and became the 1...