Main article: Martial

law under Ferdinand Marcos

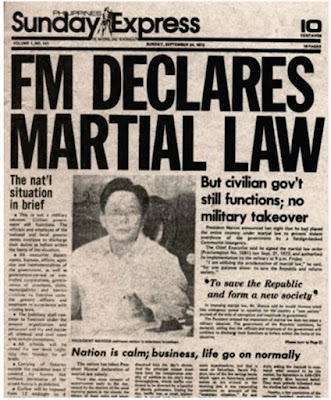

September 24, 1972 issue of the Sunday edition of the

Philippine Daily Express

Proclamation 1081

Marcos' declaration of martial law became known to the public on

September 23, 1972 when his Press Secretary, Francisco Tatad, announced on

Radio that Proclamation № 1081,

which Marcos had supposedly signed two days earlier on September 21, had come

into force and would extend Marcos's rule beyond the constitutional two-term

limit. Ruling by decree, he almost dissolved press freedom and

other civil liberties to

add propaganda machine, closed down Congress and media establishments, and

ordered the arrest of opposition leaders and militant activists, including

senators Benigno Aquino Jr., Jovito Salonga and Jose Diokno. However, unlike Ninoy Aquino's

senator colleagues who were detained without charges, Ninoy, together with

communist NPA leaders Lt Corpuz and Bernabe Buscayno, was charged with murder,

illegal possession of firearms and subversion. Marcos claimed that martial

law was the prelude to creating his Bagong Lipunan, a "New

Society" based on new social and political values.

Bagong Lipunan (New Society)

Marcos had a vision of a Bagong Lipunan (New Society)

similar to Indonesian president Suharto's "New Order

administration", China leader Mao Zedong's Great Leap Forward

and Korean Kim Il-Sung's Juche.

He used the years of martial law to implement this vision. According to

Marcos's book Notes on the New Society, it was a movement urging

the poor and the privileged to work as one for the common goals of society and

to achieve the liberation of the Filipino people through self-realization.

University

of the Philippines Diliman economics professor and former NEDA Director-General

Dr. Gerardo Sicat, an MIT Ph.D.

graduate, portrayed some of Martial Law's effects as follows:

Economic reforms suddenly became

possible under martial law. The powerful opponents of reform were silenced and

the organized opposition was also quilted. In the past, it took enormous

wrangling and preliminary stage-managing of political forces before a piece of

economic reform legislation could even pass through Congress. Now it was

possible to have the needed changes undertaken through presidential decree.

Marcos wanted to deliver major changes in an economic policy that the

government had tried to propose earlier.

The enormous shift in the mood of the

nation showed from within the government after martial law was imposed. The

testimonies of officials of private chambers of commerce and of private

businessmen dictated enormous support for what was happening. At least, the

objectives of the development were now being achieved...

Japanese imperial army soldier Hiroo Onoda offering his military sword

to Marcos on the day of his surrender on March 11, 1974

The Marcos regime instituted a

mandatory youth organization, known as the Kabataang Barangay,

which was led by Marcos's eldest daughter Imee. Presidential Decree 684,

enacted in April 1975, required that all youths aged 15 to 18 be sent to remote

rural camps and do volunteer work.

1973 Martial Law Referendum

Martial Law was put on vote in July 1973

in the 1973

Philippine Martial Law referendum and was marred with

controversy resulting to 90.77% voting yes and 9.23% voting no.

Rolex 12 and the military

Along with Marcos, members of

his Rolex 12 circle like Defense

Minister Juan Ponce Enrile,

Chief of Staff of the Philippine Constabulary Fidel Ramos, and Chief of Staff of the Armed

Forces of the Philippines Fabian Ver were the chief administrators

of martial law from 1972 to 1981, and the three remained President Marcos's

closest advisers until he was ousted in 1986. Other peripheral members of

the Rolex 12 included Eduardo

"Danding" Cojuangco Jr. and Lucio Tan.

Between 1972 and 1976, Marcos

increased the size of the Philippine military from 65,000 to 270,000 personnel,

in response to the fall of South Vietnam to the communists and the growing tide

of communism in South East Asia. Military officers were placed on the boards of

a variety of media corporations, public utilities, development projects, and

other private corporations, most of whom were highly educated and well-trained

graduates of the Philippine Military Academy. At the same time, Marcos made

efforts to foster the growth of a domestic weapons manufacturing industry and

heavily increased military spending.

Many human rights abuses were

attributed to the Philippine

Constabulary which was then headed by future president Fidel Ramos. The Civilian

Home Defense Force, a precursor of Civilian Armed Forces

Geographical Unit (CAFGU), was organized by President Marcos to battle with the

communist and Islamic insurgency problem, has particularly been accused of

notoriously inflicting human right violations on leftists, the NPA, Muslim

insurgents, and rebels against the Marcos government. However, under

martial law the Marcos administration was able to reduce violent urban crime,

collect unregistered firearms, and suppress communist insurgency in some areas.

U.S. foreign policy and martial law under Marcos

By 1977, the armed forces had

quadrupled and over 60,000 Filipinos had been arrested for political reasons.

In 1981, Vice President George H. W. Bush praised Marcos for his

"adherence to democratic principles and to the democratic processes". No

American military or politician in the 1970s ever publicly questioned the

authority of Marcos to help fight communism in South East Asia.

From the declaration of martial law

in 1972 until 1983, the U.S. government provided $2.5 billion in bilateral

military and economic aid to the Marcos regime, and about $5.5 billion through

multilateral institutions such as the World Bank.

In a 1979 U.S. Senate report,

it was stated that U.S. officials were aware, as early as 1973, that Philippine

government agents were in the United States to harass Filipino dissidents. In

June 1981, two anti-Marcos labor activists were assassinated outside of a union

hall in Seattle. On at least one occasion, CIA agents

blocked FBI investigations

of Philippine agents.

Withdrawal of Taiwan relations in favor of the People's

Republic of China.

Main articles: Philippines–Taiwan

relations and China–Philippines

relations

Prior to the Marcos administration,

the Philippine government had maintained a close relationship with the Kuomintang-ruled Republic of China (ROC) government which

had fled to the island of Taiwan,

despite the victory of the Communist Party of

China in the 1949 Chinese

Communist Revolution. Prior administrations had seen the People's

Republic of China (PRC) as a security threat, due to its

financial and military support of Communist rebels in the country.

By 1969, however, Ferdinand Marcos

started publicly asserting the need for the Philippines to establish a

diplomatic relationship with the People's

Republic of China. In his 1969 State of the Nation Address, he said:

We, in Asia must strive toward a

modus vivendi with Red China. I reiterate this need, which is becoming more

urgent each day. Before long, Communist China will have increased its striking

power a thousand fold with a sophisticated delivery system for its nuclear

weapons. We must prepare for that day. We must prepare to coexist peaceably

with Communist China.

— Ferdinand Marcos, January 1969

In June 1975, President Marcos went

to the PRC and signed a Joint Communiqué normalizing relations between the

Philippines and China. Among other things, the Communiqué recognizes that

"there is but one China and that Taiwan is an integral part of Chinese

territory…" In turn, Chinese Prime Minister Zhou Enlai also pledged that China would

not intervene in the internal affairs of the Philippines nor seek to impose its

policies in Asia, a move which isolated the local communist movement that China

had financially and militarily supported.

The Washington Post in an interview with former Philippine Communist Party

Officials, revealed that, "they (local communist party officials) wound up

languishing in China for 10 years as unwilling "guests" of the

(Chinese) government, feuding bitterly among themselves and with the party

leadership in the Philippines".

The government subsequently captured

NPA leaders Bernabe Buscayno in

1976 and Jose Maria Sison in

1977.

First parliamentary elections after martial law declaration

The 1978

Philippine parliamentary election was held on April 7, 1978 for

the election of the 166 (of the 208) regional representatives to the Interim Batasang

Pambansa (the nation's first parliament). The elections were

participated by several parties including Ninoy Aquino's newly formed party,

the Lakas ng Bayan (LABAN)

and the regime's party known as the Kilusang Bagong

Lipunan (KBL).

The Ninoy Aquino's LABAN party

fielded 21 candidates for the Metro Manila area including Ninoy himself and

Alex Boncayao, who later was associated with Filipino communist death squad

Alex Boncayao Brigade that killed U.S. army Colonel James N. Rowe. All of the party's candidates,

including Ninoy, lost in the election.

Marcos's KBL party won 137 seats,

while Pusyon Bisaya led by Hilario Davide Jr.,

who later became the Minority Floor Leader, won 13 seats.

Prime Minister

In 1978, the position returned when

Ferdinand Marcos became Prime Minister. Based on Article 9 of

the 1973 constitution, it had broad executive powers that would be typical of

modern prime ministers in other countries. The position was the official head

of government, and the commander-in-chief of the armed forces. All of the

previous powers of the President from the 1935 Constitution were transferred to

the newly restored office of Prime Minister. The Prime Minister also acted as head

of the National Economic Development Authority. Upon his re-election to the

Presidency in 1981, Marcos was succeeded as Prime Minister by an

American-educated leader and Wharton graduate, Cesar Virata, who was elected as an

Assemblyman (Member of the Parliament) from Cavite in 1978. He is the eponym of

the Cesar Virata School of Business, the business school of the University

of the Philippines Diliman.

Proclamation No. 2045

After putting in force amendments to the constitution, legislative

action, and securing his sweeping powers and with the Batasan, his supposed

successor body to the Congress, under his control, President Marcos

issued Proclamation 2045, which technically "lifted"

martial law, on January 17, 1981.

However, the suspension of the

privilege of the writ of habeas corpus continued

in the autonomous regions of Western Mindanao and Central Mindanao. The opposition dubbed the

lifting of martial law as a mere "face lifting" as a precondition to

the visit of Pope John Paul II.

Third term (1981–1986)

Main article: 1981 Philippine presidential election and referendum

President Ferdinand E. Marcos in Washington in 1983.

We love your adherence to democratic

principles and to the democratic process, and we will not leave you in

isolation.

— U.S. Vice President George H. W. Bush during Ferdinand E.

Marcos inauguration, June 1981

On June 16, 1981, six months after

the lifting of martial law, the first presidential election in twelve years was

held. President Marcos ran and won a massive victory over the other candidates.

The major opposition parties, the United

Nationalists Democratic Organizations (UNIDO), a coalition of

opposition parties and LABAN, boycotted the elections.

After the lifting of Martial Law, the

pressure on the Communist CPP-NPA alleviated. The group was able to return to

urban areas and form relationships with legal opposition organizations, and

became increasingly successful in attacks against the government throughout the

country. The violence inflicted by the communists reached its peak in 1985

with 1,282 military and police deaths and 1,362 civilian deaths.

Aquino's assassination

Main article: Assassination

of Benigno Aquino Jr.

On August 21, 1983, opposition

leader Benigno Aquino Jr. was

assassinated on the tarmac at Manila

International Airport. He had returned to the Philippines after

three years in exile in the United States, where he had a heart bypass

operation to save his life after Marcos allowed him to leave the Philippines to

seek medical care. Prior to his heart surgery, Ninoy, along with his two

co-accused, NPA leaders Bernabe Buscayno (Commander Dante) and

Lt. Victor Corpuz, were sentenced to death by a military commission on charges

of murder, illegal possession of firearms and subversion.

A few months before his

assassination, Ninoy had decided to return to the Philippines after his

research fellowship from Harvard University had

finished. The opposition blamed Marcos directly for the assassination while

others blamed the military and his wife, Imelda. Popular speculation pointed to

three suspects; the first was Marcos himself through his trusted military chief

Fabian Ver; the second theory pointed to his wife Imelda who had her own

burning ambition now that her ailing husband seemed to be getting weaker, and the

third theory was that Danding Cojuangco planned

the assassination because of his own political ambitions. The 1985

acquittals of Chief of Staff General Fabian Ver as well as other high-ranking

military officers charged with the crime were widely seen as a whitewash and

a miscarriage of justice.

On November 22, 2007, Pablo Martinez,

one of the convicted suspects in the assassination of Ninoy Aquino Jr. alleged

that it was Ninoy Aquino Jr.'s relative, Danding Cojuangco, cousin of his wife

Corazon Cojuangco Aquino, who ordered the assassination of Ninoy Aquino Jr.

while Marcos was recuperating from his kidney transplant. Martinez also alleged

only he and Galman knew of the assassination, and that Galman was the actual

shooter, which is not corroborated by other evidence of the case.

Impeachment attempt.

In August 1985, 56 Assemblymen signed

a resolution calling for the impeachment of President Marcos for

alleged diversion of U.S. aid for personal use, citing a July 1985 San Jose Mercury News exposé

of the Marcos's multimillion-dollar investment and property holdings in the

United States.

The properties allegedly amassed by

the First Family were the Crown Building, Lindenmere Estate, and a number of

residential apartments (in New Jersey and New York), a shopping center in New

York, mansions (in London, Rome and Honolulu), the Helen Knudsen Estate in

Hawaii and three condominiums in San Francisco, California.

The Assembly also included in the

complaint the misuse and misapplication of funds "for the construction of

the Manila Film Center,

where X-rated and pornographic films are exhibited, contrary to public

morals and Filipino customs and traditions." The impeachment attempt

gained little real traction, however, even in the light of this incendiary

charge; the committee to which the impeachment resolution was referred did not

recommend it, and any momentum for removing Marcos under constitutional

processes soon died.

Thanks for reading.

No comments:

Post a Comment